The

Caprichos

&

Caricature

excerpted

from

the

book

Saturn:

An

essay

on

Goya

By

Andrè

Malraux

Phaidon

Publishers,

1957,

translated

from

the

French

by

C.

W.

Chilton,

excepted

are

pages

46

–

54

For

ages Spain

had felt

herself

to be an

abettor

of the higher

diabolism.  Philip

II had peopled

the vistas

of the catacombs

that guarded

his solitude

with the

creations

of Bosch.

And who

but Bosch

and Bruegel

had forestalled

Goya in

summoning

such convincing

monsters

from unplumbed

depths?

And Bruegel

did not

surpass

the vividness

of the Temptations

until, in

the Dulle

Griet he met the

Scourge,

the maddened

slut let

loose in

a fiery,

seething

mass of

misery.

But like

him and

like Bosch,

Goya seemed

not to hear

anything

now but

the murmuring

of his secret

language.

What he

did understand

was that

his enemy

was the

Creation.

Following

the Flemish

diabolists

he fought

against

it with

satirical

fantasy.

He knew

now –

and he was

the first

to know

it for three

hundred

years –

that his

world would

never replace

the real

except by

a new system

of relationships

between

things and

beings.

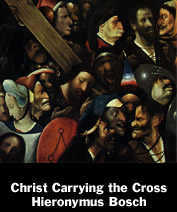

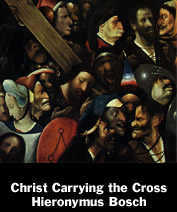

Bosch painted

men-horses,

demon-fish,

roundel-hats

and gave

life to

their strange

world by

thrusting

it into

time, by

giving crutches

to his devils

(wounded

in what

battles?),

and by plunging

it into

space; the

damned,

made of

shellfish

and eggshells,

fall for

ever into

the depths

of a background

that Bosch

was picturing

at about

the same

time as

Leonardo

was working;

they fall

in a hellish

evening

as clear

as the twilight

of our infancy,

in a hellish

night in

which, behind

the sad

face of

mankind,

there turns

windmills

with sails

of fire,

a night

more charged

with poetry

that the

burning

of Rome.

Philip

II had peopled

the vistas

of the catacombs

that guarded

his solitude

with the

creations

of Bosch.

And who

but Bosch

and Bruegel

had forestalled

Goya in

summoning

such convincing

monsters

from unplumbed

depths?

And Bruegel

did not

surpass

the vividness

of the Temptations

until, in

the Dulle

Griet he met the

Scourge,

the maddened

slut let

loose in

a fiery,

seething

mass of

misery.

But like

him and

like Bosch,

Goya seemed

not to hear

anything

now but

the murmuring

of his secret

language.

What he

did understand

was that

his enemy

was the

Creation.

Following

the Flemish

diabolists

he fought

against

it with

satirical

fantasy.

He knew

now –

and he was

the first

to know

it for three

hundred

years –

that his

world would

never replace

the real

except by

a new system

of relationships

between

things and

beings.

Bosch painted

men-horses,

demon-fish,

roundel-hats

and gave

life to

their strange

world by

thrusting

it into

time, by

giving crutches

to his devils

(wounded

in what

battles?),

and by plunging

it into

space; the

damned,

made of

shellfish

and eggshells,

fall for

ever into

the depths

of a background

that Bosch

was picturing

at about

the same

time as

Leonardo

was working;

they fall

in a hellish

evening

as clear

as the twilight

of our infancy,

in a hellish

night in

which, behind

the sad

face of

mankind,

there turns

windmills

with sails

of fire,

a night

more charged

with poetry

that the

burning

of Rome.

Goya,

for his

part, represents

a simpleton

being shaved

by women

who skin

him, adds

to carnival

the mummery

of the Inquisition;

tired of

putting

masks on

his characters

he turns

the face

into a mask,

or into

an animal,

or replaces

it with

an animal's

head; gives

asses human

gestures;

combines

man and

beast for

his Sorcerers

Out Walking; invents

the Chinchilla,

a man with

padlocks

for ears;

discovers

the spectral

voice of

draped figures

clothing

themselves

in the void;

enlarges

the hands

of the Goblins.

Life is

given to

all this

by its irony

and by the

appearance

in an unusual

setting

of familiar

sentiments

which snatch

these scenes

out of the

moment and

extend them

in life

of their

own; sorcerers

and demons

must cut

their nails;

ghosts watch

for the

coming of

day so that

they can

flee in

time. But

Goya disposed

also of

an obscure

people that

the Flemish

had not

known –

a people

which was

not, strictly

speaking,

imagined

but rather

intercepted.

Did he himself

distinguish

between

the monsters

that he

owed to

the combinations

taken from

a revived

tradition,

the Sorcerers

Out Walking for example,

and those

brought

to him from

he depths

of ages

by sleep

and especially

by dreaming.

The enormous

hand of the Goblins, and the

clothes

without

a face are

well known

to psycho-analysts;

the plucked

man-chicken

is one of

the strange

beasts that

they are

still discussing

and one

which the

unconscious

seems to

bring up

from its

deepest

depths.

Saturn has

always been

the god

of witchery.

Caricaturists

in all humanity

want to

reduce the

world to

one single

meaning,

to reveal

what it

hides by

isolating

it from

what is

hidden;

Goya wanted

to extend

it, to add

that which

would prolong

it into

regions

of mystery.

He does

not illuminate

it like

a moralist,

a pamphleteer,

or a satirist;

the light

which he

lets down,

instead

of illuminating

the puppets,

stretches

their immense

shadows

out over

infinity.

In his time

Bosch and

Bruegel

were counted

among the

caricaturists

(as Baudelaire

was to count

them later);

the distortion

which was decisively

breaking

away from

reality

had already

learnt how

to get back

to the supernatural.

Stylized

as the art

of this

period may

have been,

and in spite

of Fragonard

and David,

illusion

– the

'objective

vision',

it may be,

of the imaginary

– played

a preeminent

part in

it. The

modesty

of caricature

freed it

from this.

Being a

two-dimensional

art, like

those of

the ante-classical

era, it

did not

attempt

to compete

with the

real while

it resembled

it. It still,

however,

remained

obedient

to it. But

if we look

at the first Caprichos after seeing

an album

of contemporary

caricatures

we are gripped

by the presence

of a new

dimension

which is

by no means

that of

depth.

Of

course,

there is

a kind of depth

in the Caprichos, but it is

not that

of 'reality',

or that

of the Italians

(Goya's

distance

is not an

horizon).

It is a

depth of

lighting

– which

caricature

did not

possess,

consisting

as it did

of lines

or low relief,

sometimes

coloured

in flat

tints. Nor

does Goya's

lighting

tend to

build up

space. Like

that of

Rembrandt,

and of the

cinema,

it tends

to connect

that which

it marks

off from

the shadow

and to give

it a a meaning

that goes

beyond it,

and, to

be precise,

transcends

it. The

darkness

is not merely

black, it

is also

darkness.

Copyright

©1957

Phaidon

Press Ltd.