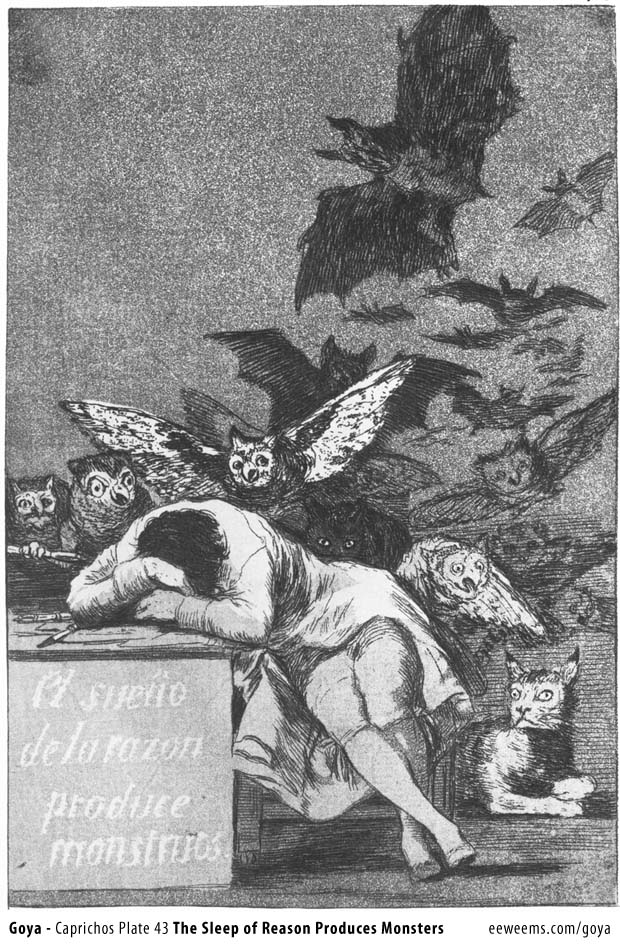

Caprichos Plate 43

The Sleep of Reason

Produces Monsters

21.6cm x 15.2cm

12.5" x 8.75" inches (uncut sheet)

8.5" x 6" inches (published sheet)

Text caption from the "Prado" etching version:

"Fantasy abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters: united with her, she is the mother of the arts and the origin of their marvels."

"La fantasia abandonada de la razon, produce monstruos imposibles: unida con ella, es madre de las artes y origen de sus marabillas."

Apologies to Francisco de Goya

List of Plates:

Plate 43

The sleep of reason

Plate 2

They Say Yes

Plate 33

To the Count Palantine

Plate 55

Until Death

Plate 77

First One, Then Another

THE CAPRICHOS

There are minor disagreements among art historians about the Caprichos. That Goya worked on the Caprichos sets for several years before publishing them in 1799 is clear, but the certain date of when he began the series is not known.

Fred Licht's book Goya, says Goya began laboring on this set in 1797; Reva Wolf's book Goya and the Satirical Print says he was laboring on it in 1796; Xavier de Salas' Goya quotes two sources showing that Goya began preparing the Caprichos in 1793. Whatever the case, the Philip Hofer introduction to the Dover Books edition of Los Caprichos says that Goya sold 27 sets (in two days) across the street from his home at a shop for perfume and liquors. Sarah Symmon's book Goya says the prints were sold in a liqueur & scent shop which was downstairs from Goya's Madrid apartment.

The usual legend about the Caprichos is that after two days Goya personally withdrew the remaining unsold sets (approximately 270). The public reaction was apparently quite negative and was enough for Goya to fear legal repercussions, if not actually coming under the power of the Inquisition itself. Robert Hughes book, Goya, however, states there is no evidence for this turn of events, that instead the Caprichos were simply unpopular, that Goya could not get them into even Madrid bookstores, their proper outlet. Sarah Symmon's book says that in 1803 he donated the unsold sets, along with the copper plates, to the Royal print works as part of a deal to secure a pension for his son Xavier. She also states that Goya, later in life, said that he withdrew the Caprichos out of fear of the Inquisition. Frank Milner's book (also simply titled Goya) carries this same chronology of events, but Milner simply says that the etching sets were priced too highly (320 Spanish reales, roughly the equivalent to an ounce of gold) and there was not a very large audience for the deeply thought-out allusions that Goya imbued the Caprichos with.

The entire set of some 80 prints cover subjects of prostitution, child sexual abuse, witchcraft, numerous specific superstitions, and satiric critiques of doctors, politicians, and clergy, among others. Nearly half of the imagery concerns itself with witchcraft, often in a mocking tone that shows that Goya's use of this particular subject was meant to have more than just one single understanding for the viewer.

Some writers on Goya have called this symbolic multifaceted"visual language" that Goya employs as "code." Obviously, viewing pictures about Spanish culture in 1799 carries a number of pitfalls for the modern 21st century viewer - - hence the industry of interpretation that exists to explain the Caprichos, much of it in frankly Freudian terms, which may reflect more heavily the 21st century western culture trying to find meaning in the pictures, versus the actual meanings Goya figured upon as part of his 18th century world.

In his old age, while in exile in France, it was suggested to Goya that he have the Caprichos reprinted again. He responded that he no longer owned the plates, and that besides, 'he had better ideas now.'

For a relatively straight-forward explanation of the Caprichos and it's themes, be sure to read the brief paper that accompanied a Caprichos exhibit at Columbia University in 1993 (brief excerpt below):

"The series known as "Los Caprichos," which, loosely translated, means "the caprices," shows Goya's rancor at the unpredictability of life, combining acerbic commentary on the Spanish aristocracy, the clergy and human nature itself with images of monsters, ghouls and other supernatural figures."

AMAZON

Goya The Terrible Sublime - Graphic Novel - (Spanish Edition) - Amazon

"From this headlong seizure of life we should not expect a calm and refined art, nor a reflective one. Yet Goya was more than a Nietzschean egoist riding roughshod over the world to assert his supermanhood. He was receptive to all shades of feeling, and it was his extreme sensitivity as well as his muscular temerity that actuated his assaults on the outrageous society of Spain." From Thomas Craven's essay on Goya from MEN OF ART (1931).

"...Loneliness has its limits, for Goya was not a prophet but a painter. If he had not been a painter his attitude to life would have found expression only in preaching or suicide." From Andre Malroux's essay in SATURN: AN ESSAY ON GOYA (1957).

"Goya is always a great artist, often a frightening one...light and shade play upon atrocious horrors." From Charles Baudelaire's essay on Goya from CURIOSITES ESTRANGERS (1842).

"[An] extraordinary mingling of hatred and compassion, despair and sardonic humour, realism and fantasy." From the foreword by Aldous Huxley to THE COMPLETE ETCHINGS OF GOYA (1962).

"His analysis in paint, chalk and ink of mass disaster and human frailty pointed to someone obsessed with the chaos of existence..." From the book on Goya by Sarah Symmons (1998).

"I cannot forgive you for admiring Goya...I find nothing in the least pleasing about his paintings or his etchings..." From a letter to (spanish) Duchess Colonna from the French writer Prosper Merimee (1869).

GOYA : Los Caprichos - Dover Edition - Amazon