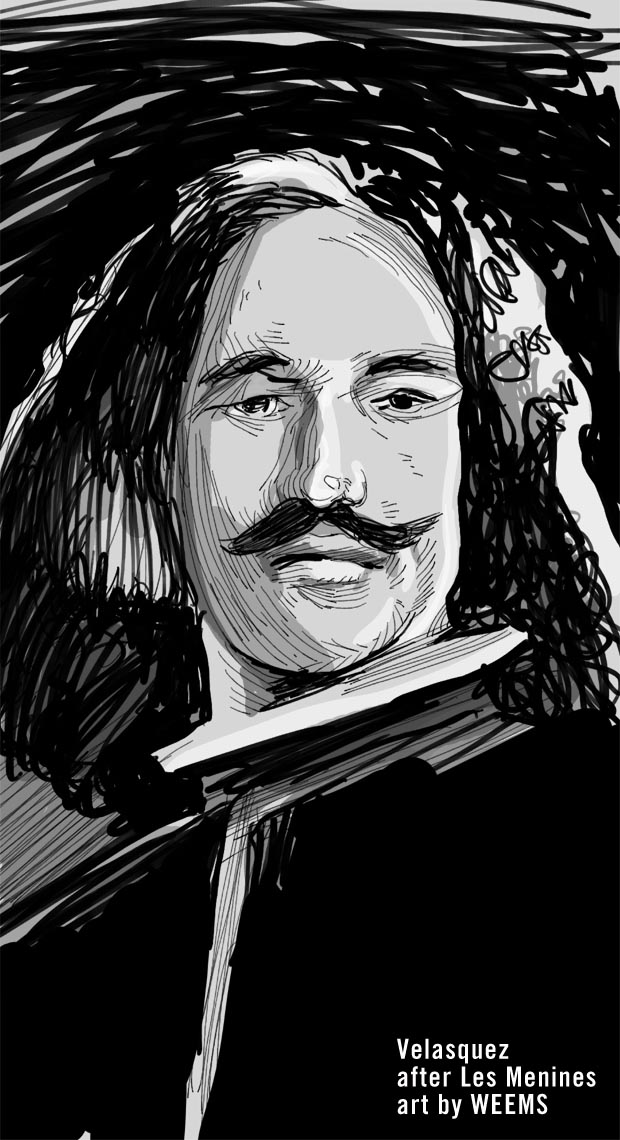

Goya and Velàsquez

Las Meninas

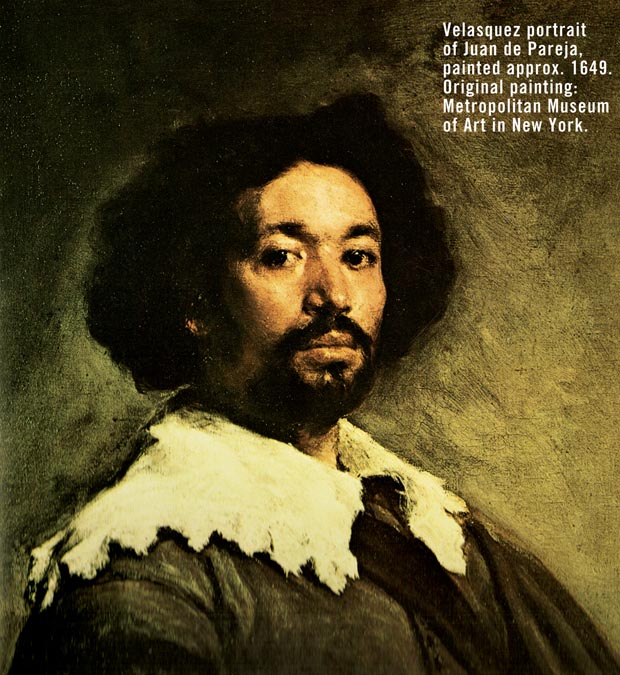

Velasquez portrait of Juan de Pareja,

Velasquez portrait of Juan de Pareja,

painted approx. 1649.

The original painting is in the

Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Diego Velasquez "the faultless painter"

"Velasquez, painter of Spain's worldly pride and power, of the pomp and panoply of that brief moment in the 17th Century when the nation stood boldly, if insecurely, at the center of the historical stage. He, like his country, is confident of his power – a serene realist, sure of his vision, his technical mastery, his place in the life of his times."

(Page 7, The World of Goya, by Richard Schickel, Time-Life Books 1968)

"Velasquez has next to no personal myth. We know so little about him that he almost vanishes behind his paintings – not at all an unhealthy situation in an age obsessed and blinded by 'personality' and celebrity, but one that makes it difficult for people raised on late-twentieth-century ideas of artistic achievement to approach. What was he 'really' like? We do not know and never will."

(Page 19, Goya, by Robert Hughes, published by Alfred Knopf, 2003)

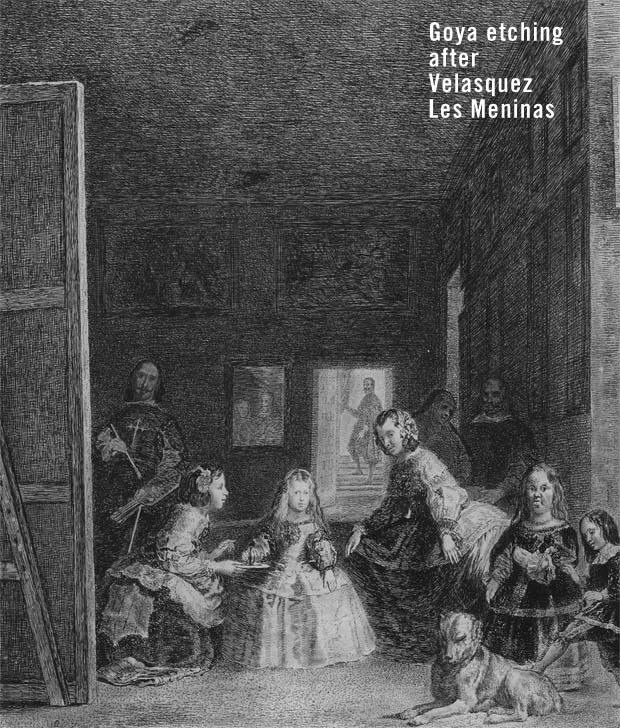

Goya's etched copy of the Las Meninas Velasquez painting

Goya claimed that his teachers were "nature, Rembrandt and Velasquez." (Page 22, Goya, by Bernard L. Myers, Spring Books, 1964)

Goya made a number of copies of Velasquez images. The list below is based on the "Complete Etchings of Goya" book, miscellany appendix:

Etched copies of:

Las Meninas

Philip III

Margaret of Austra

Philip IV

Isabel of Bourbon

A Prince of Spain (1st state)

A Prince of Spain (2nd state)

Pernia, Called Barberousse

The Buffoon Don Juan of Austria

Ochoa, Porter of the Palace (1st state)

Ochoa, Porter of the Palace (2nd state)

Aesop

Menippus

Gathering of the Drinkers

D. Baltasar Carlos

D. Gaspar de Guzman, Count of Olivares

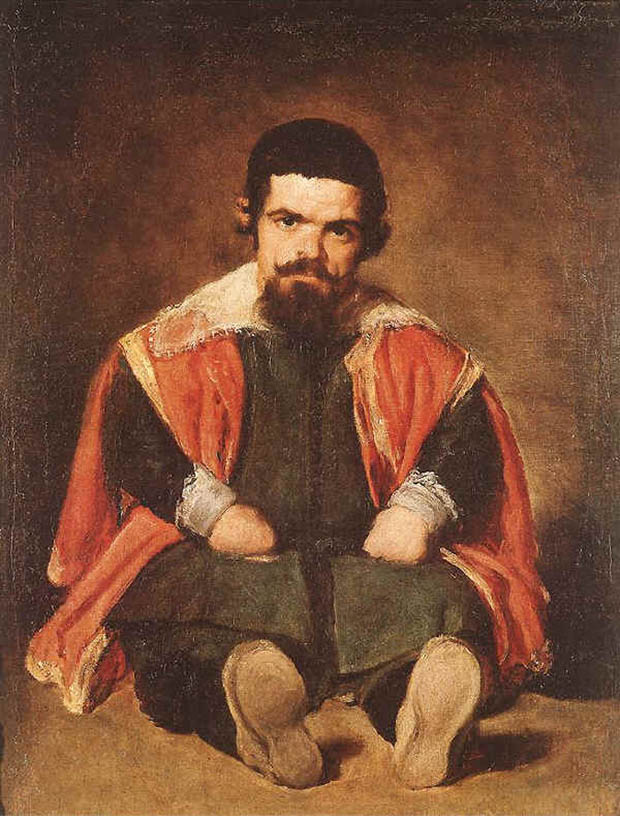

The Dwarf Sebastian of Morra

The Dwarf El Primo

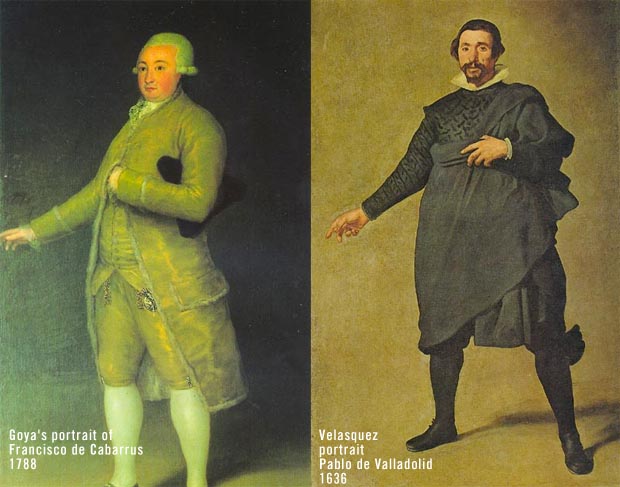

A comparison

For Goya's portrait of Francisco de Cabarrus (1788), he is reported to have studied the Velasquez portrait of Pablo de Valladolid (1636). Click on the images below to enlarge:

Some background from biographers:

"...for several months he felt unable to undertake work on the scale of the tapestry cartoons. Instead, he turned to etching , a technique that he had probably learned earlier. He set about the task of copying 16 of Velasquez' paintings in the royal collections. As copies they were not successful – Goya could not help but try his own variations on the master's work – but the careful study he made of the originals had a profound effect on him. Until this moment he had inexplicably paid little attention to this greatest of Spanish masters. He undoubtedly knew Velasquez, but never before had he confronted him so directly. Now he perceived in Velasquez' work a native tradition far better suited to his own temperament than anything in the contemporary styles. Moreover, he saw that Velasquez was a painter who had, a century earlier, practiced what the Enlightenment was now preaching – the close scrutiny of nature, in particular human nature – and that he had a psychological awareness that none of Goya's contemporaries approached.

Goya labored far longer over his copying than the job required. In the process, almost incidentally, he developed the technical skills that were to make him one of the greatest graphic artists the world has ever known."

Page 54, The World of Goya, by Richard Schickel, Time-Life Books 1968.

"Although Goya never completed the larger set of prints that he had originally contemplated producing, he was sufficiently satisfied with his set of nine etched portraits after Velasquez to advertise them for sale in July in the official government newspaper, the Graceta de Madrid. In December he offered a further two printed copies after Velasquez."

Page 73, Goya, by Sarah Symmons, Phaidon Press, 1998.

"...He was ordered to engrave a series of from the Velasquez in the royal collection. This gave him the chance to move freely and study at will among the King's pictures, and he came to know intimately those works by Velasquez, Rubens and Rembrandt to which later he was to declare his great debt."

(Page 8, Goya, by Bernard L. Myers, Spring Books, 1964)

"His painting has undeniable influences of Velasquez, according to Yraider, his first biographer, a noticeable thing in his large fulsome portraits, because also in Goya one finds atmosphere, light, life, power and delicacy of tone. Nevertheless Velasquez is nobler and has greater epic qualities, Goya plainer. It is true that the epic quality had disappeared from the Court, for now no Phillip IV reigned but Carlos IV, there was now no Marianne of Austria but Maria Luisa of Parma, in place of the Duke of Olivares was Manuel Godoy."

(Page 2 of the English language translation from Goya, Ediciones Minos, Museo del Prado, 1961)

Note: You'll notice that the biographers disagree on how many direct copies Goya made from Velasquez. I have read that it is as few as six completed images; or nine images with only six surviving; Xavier de Salas book says 13 images, and as you would have read above, Schickels Time-Life book says 16 altogether. The book Complete Etchings of Goya (Crown Publishers), shows 18 etchings after Velasquez, with two being secondary versions (i.e., Goya apparently changed the printing method and emphasized features that are much weaker in the first state versions.)

Goya's etching copy of Velasquez' painting

Goya's etching copy of Velasquez' painting

"Dwarf upon the floor," usually

identified as Sebastian de Morra. Called "The Dwarf El Primo" in the Complete Etchings of Goya book.

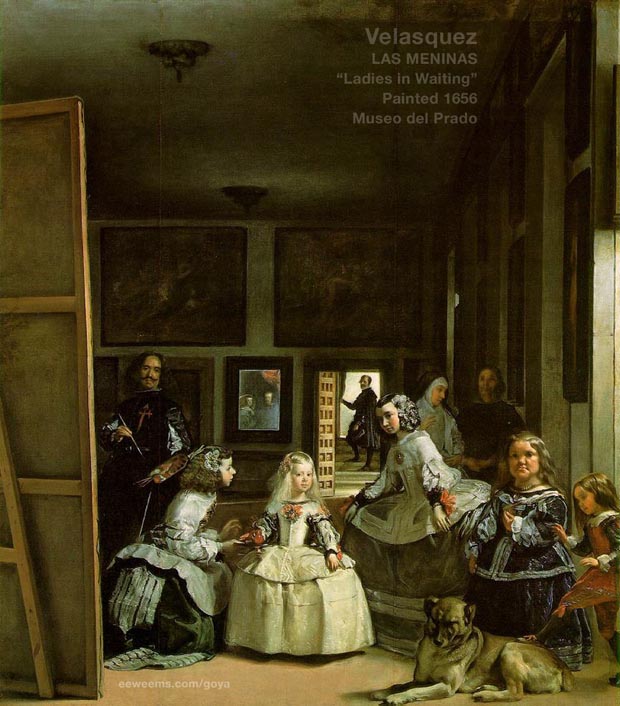

"...one must consider the significance of Goya's seemingly clumsy use of a compositional prototype: Velasquez's Meninas. A single glance at the general construction of the two paintings is enough to prove this universally accepted fact. In both pictures the painter himself stands at a slightly inclined canvas at stage left; in both pictures the prospect is closed off by two large canvases hung on the rear wall; in both pictures the major figures are disposed in a very loose arrangement centering on a female figure brilliantly costumed (the Infanta in the Velasquez, Maria Luisa in the Goya), who, her head slightly cocked, stares straight out of the picture.

Rarely, if ever before, has a painter referred so pointedly to the work of a predecessor."

From "Goya's Portrait of the Royal Family," by

Fred Licht, Art Bulletin, Vol. 49, No. 2 (June 1967), pp. 127-128.

Goya used the subject of the reflective powers of mirrors as a running theme through several pieces. Perhaps the most well known is his painting Las Vierjas (also called Que Tal? and simply Time). Fred Licht (among others) has pointed out the similarity of the flat rectangular mirror to the flat rectangular canvas, and how close the two are in function in certain pieces, especially Goya's The Family of King Carlos IV, where Goya seems to indicate that the viewer is in the position of a mirror upon which the subjects gaze, i.e., the painting is the mirrored reflection, not the actual setting (which, incidentally, includes Goya himself, much the way that the earlier great Spanish painter Velasquez had included himself into his painting Las Meninas).

AMAZON

Goya The Terrible Sublime - Graphic Novel - (Spanish Edition) - Amazon

"From this headlong seizure of life we should not expect a calm and refined art, nor a reflective one. Yet Goya was more than a Nietzschean egoist riding roughshod over the world to assert his supermanhood. He was receptive to all shades of feeling, and it was his extreme sensitivity as well as his muscular temerity that actuated his assaults on the outrageous society of Spain." From Thomas Craven's essay on Goya from MEN OF ART (1931).

"...Loneliness has its limits, for Goya was not a prophet but a painter. If he had not been a painter his attitude to life would have found expression only in preaching or suicide." From Andre Malroux's essay in SATURN: AN ESSAY ON GOYA (1957).

"Goya is always a great artist, often a frightening one...light and shade play upon atrocious horrors." From Charles Baudelaire's essay on Goya from CURIOSITES ESTRANGERS (1842).

"[An] extraordinary mingling of hatred and compassion, despair and sardonic humour, realism and fantasy." From the foreword by Aldous Huxley to THE COMPLETE ETCHINGS OF GOYA (1962).

"His analysis in paint, chalk and ink of mass disaster and human frailty pointed to someone obsessed with the chaos of existence..." From the book on Goya by Sarah Symmons (1998).

"I cannot forgive you for admiring Goya...I find nothing in the least pleasing about his paintings or his etchings..." From a letter to (spanish) Duchess Colonna from the French writer Prosper Merimee (1869).

GOYA : Los Caprichos - Dover Edition - Amazon