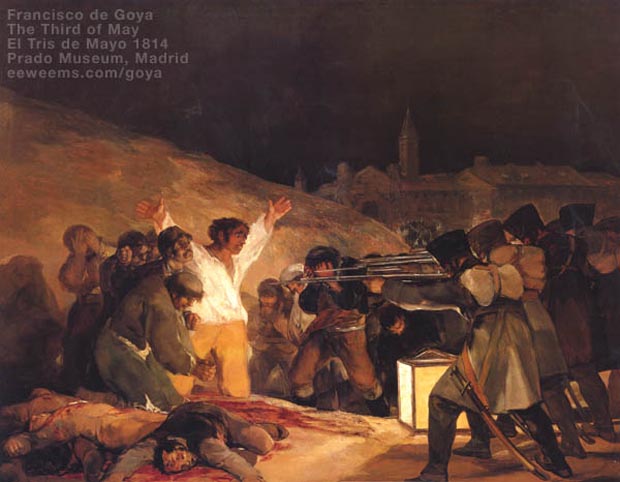

Goya | The Third of May

El Tres de Mayo

The Third of May

El Tres de Mayo

1814 Oil on canvas

104 1/2 inches by 135 3/4 inches

266cm x 345cm

Prado Museum, Madrid

This image shows the random executions of the Spanish citizenry resulted from the fighting in the Puerto del Sol area of Madrid (Also see the Goya painting Second of May). A national uprising in Spain followed, and scenes such as Goya's 'Third of May' were repeated throughout the Spanish countryside, as the French commanders failed to quell the national mood, and instead made it more furious.

Goya had previously admired the practical freedoms the French "enlightenment" had promised. Most of the Spanish intellectuals of Goya's time were weary of the faltering efforts of Charles IV and Ferdinand to bring reform and improvement to Spain. However, the brutality of Napoleon (through his brother Joseph and the military commanders instructed to minimize the fighting there) suspended whatever affection the Spanish liberals had for French freedoms.

For the length of the six-year occupation by the French, Goya lived almost entirely in Madrid. There is much speculation in art books about whether Goya personally witnessed events such as 'The Second of May,' and 'The Third of May." It is evident that Goya owned property at La Quinta, where the massacres took place, and there is (though disputed by some historians) a story by one of Goya's gardeners, a man named Isidro, who told Antonio Trueba (recorded in his book Madrid por fuera Amazon) that Goya witnessed the shooting at Montana del Principe Pio via telescope (note: there was a telescope inventoried as belonging to Goya after his death), and that Isidro accompanied Goya later that night to the place where the corpses were, at which time Goya made notes. This account is referenced in Xavier de Salas book GOYA (Goya / Xavier de Salas ; [translation, G. T. Culverwell] Amazon

)

"...the Third of May, has become even more famous, haunting the covers of history books, appearing on postage stamps and postcards. It has been used to epitomize the art of Goya, as well as the spirit of Spanish revolutionary heroism. This violent yet moving image depicts the public execution of insurgents on 3 May 1808, the day following the insurrection [see Goya's The Second of May] In contrast to the vigour of the street battle, in which the Spaniards appear, momentarily, to be gaining the upper hand, this massacre of civilians, which the French carried out in reprisal for the insurrection, has been painted in the most eye-catching colours. Here, in glowing whites, golds and scarlets against the sombre blacks, greys and browns of the background, the doomed men are immortalized, the street fighters from the Second of May meet their fate. One or two are recognizable: the corpse sprawled below the living victims, a prone male figure with matted blood-soaked hair and shattered skull, is identifiable as the hero with the dagger, stabbing the horse in the right-hand foreground of the proceeding picture."

[Above] from Sarah Symmon's book, Goya,

Phaidon press, 1998. Page 263.

To read about Symmon's book, go here.

Amazon link to the book Goya Art: Ideas by Sarah Symmons

"Most of the victims have faces. The killers do not. This is one of the most often-noted aspects of the Third of May, and rightly so: with this painting, the modern image of war as anonymous killing is born, and a long tradition of killing as ennobled spectacle comes to its overdue end."

[Above] from Robert Hughes book, Goya,

Knopf Books, 2003. Page 317.

To read about Hughes' book, go here.

Amazon link to the Robert Hughes book Goya

From an email with a Napoleonic scholar:

"I went back and looked over your historical info. and it looks fine to me. I was actually pleased that you mentioned that the Spanish committed atrocities against the French as well in response for their actions. In your discussion of "Great deeds against the dead" I just wanted to mention that Spanish guerrillas and peasants were also known to have frequently unearthed dead Frenchmen and mutilated their corpses. My other comment concerns your discussion in "the Third of May." You mention the dissatisfaction that many Spanish intellectuals had with Charles and Ferdinand and you say that these two monarchs ruled unsuccessfully. Actually one of the major problems that the Spanish intellectuals had with their kings was that they refused to give their subjects a constitution (a major goal of liberals in the early 19th century). In fact, after the Napoleonic Wars were over, Ferdinand had promised to rule with a written constitution. But when he went back on this promise (he was a real jerk) -- this sparked a liberal revolt in Spain in the 1820s which was brutally suppressed." - K.G.

Goya's Third of May - Retribution and Justice

An article titled "Violence in European Paintings" by S. A. Khan was published in the Bangladesh New Nation on September 17, 2006 includes a novel interpretation of Goya's Third of May. Khan is a member of the faculty at the Presidency University at Dhaka, in Bangladesh. (The article also includes analysis of art by Delacroix' Liberty Leading the People and Gericault’s The Raft of the Medusa.)

"In The Third of May 1808, Francisco de Goya painted an event that took place on the second and third of May1808, when the citizens of Madrid rose up against the French invaders and received on the following day a swift and barbarous retribution (Honour, 602). On the left of the painting, a group of unarmed civilians kneeling in a mingled pool of blood and dead bodies, backed against a mound and facing a firing-squad; members of the firing squad, on the right, are ready and committed to carry out the executions; a group of spectators have gathered past the condemned and the executioners to witness the event. The dark sky in the background is sad and gloomy, and a palace looks lifeless and has lost all its grandeur. The only illumination in the painting comes from a lantern at the feet of the soldiers.

Initial observation arouses sympathy in our heart for the helpless men who are facing death, but careful analysis would help us understand that perhaps they do not deserve sympathy. Instead, these men are facing justice; the table of oppression has turned against them! A monk among the condemned civilians reminds us vividly of the Spanish Inquisition. Spain bathed in death and destruction, but the time has come for them to meet their fate. Goya did not show us the faces of the executioners—i.e., their identity-- because it is unimportant who is carrying out justice. Some may think those are French soldiers, but their uniforms and high hats (French soldiers wore hats with a flattened brim in front and back) do not support such view.

The civilians witnessing the execution appear to be neutral, participating in neither invasion nor in the uprising; thus, they are innocent. However, in realty, these men are treacherous individuals who benefited from being Spaniards but refused to help the motherland. Now come the cowards to witness the death of the Spanish heroes. The guilt in these weaklings is constant and as a result, they cannot make direct eye contact with the condemned men or the soldiers; one of them looks at the event through a hesitant side-glance while the others have covered their eyes with shame.

Finally, Goya, the great Spanish painter, focuses the lone lantern on the people who are dead or would be dead shortly. Therefore, it would be reasonable if we conclude the essence of this painting is death and the horror."

Hidden Goya Self-Portrait in The Third of May?

October 2003

The writer Siri Hustvedt (in a UK Guardian article here) discusses discovering a small self-portrait image of the artist in the famous painting:

"...In the foreground, bloody corpses lie on top of one another, but above those bodies are two strange people. The uppermost figure is cloaked and appears to be an older woman. Beneath her is another person, darker and more vague, a being whose contours vanish into darkness. .... I saw Goya's face staring out at me. It's a simple rendering - large eyes, flat nose and open mouth, but it includes the artist's signature leonine hair flowing out from around his jawline."

UK Guardian article here.

Original Page 1997- Update June 2019

AMAZON

Goya The Terrible Sublime - Graphic Novel - (Spanish Edition) - Amazon

"From this headlong seizure of life we should not expect a calm and refined art, nor a reflective one. Yet Goya was more than a Nietzschean egoist riding roughshod over the world to assert his supermanhood. He was receptive to all shades of feeling, and it was his extreme sensitivity as well as his muscular temerity that actuated his assaults on the outrageous society of Spain." From Thomas Craven's essay on Goya from MEN OF ART (1931).

"...Loneliness has its limits, for Goya was not a prophet but a painter. If he had not been a painter his attitude to life would have found expression only in preaching or suicide." From Andre Malroux's essay in SATURN: AN ESSAY ON GOYA (1957).

"Goya is always a great artist, often a frightening one...light and shade play upon atrocious horrors." From Charles Baudelaire's essay on Goya from CURIOSITES ESTRANGERS (1842).

"[An] extraordinary mingling of hatred and compassion, despair and sardonic humour, realism and fantasy." From the foreword by Aldous Huxley to THE COMPLETE ETCHINGS OF GOYA (1962).

"His analysis in paint, chalk and ink of mass disaster and human frailty pointed to someone obsessed with the chaos of existence..." From the book on Goya by Sarah Symmons (1998).

"I cannot forgive you for admiring Goya...I find nothing in the least pleasing about his paintings or his etchings..." From a letter to (spanish) Duchess Colonna from the French writer Prosper Merimee (1869).

GOYA : Los Caprichos - Dover Edition - Amazon